The problem

Takeaway food is typically high in energy, fat and salt and consumption is associated with body weight and weight gain. Many neighbourhoods have a high density of takeaway outlets, especially in more deprived neighbourhoods, and neighbourhoods with more takeaways amplify social inequalities in unhealthy eating and obesity.

Common public health responses to the ‘problem’ of takeaways are to support existing outlets to improve the nutritional quality of their offering, for example through healthier frying techniques, or to reduce the proliferation of outlets through planning restrictions on new outlets.

There have been some attempts to develop ‘healthier’ takeaways but these are often more expensive.

The intervention

A social enterprise in Balsall Health, Birmingham aims to provide healthy vegetarian food made from surplus.

A recent grant of £75,000 from Severn Trent enabled the company to expand their kitchen facilities, open an attached store front café, and begin operating as a takeaway in June 2023. This adds to an existing catering business for weddings and other large events, enabling subsidising of free meals for city centre distribution. The company aspires to merge a standard full price offer with ‘pay it forward’ (i.e. customers paying full price can contribute to low cost meals for others), and ‘pay what you can’ options.

In December 2023 they began selling via a fast food delivery app. Whilst the takeaway is currently a small part of the company’s business (5-10 customers/day), they have recently been awarded a small grant to support further marketing and aspire to around 100 customers a day.

The research

Overarching research question

Can we conduct an evaluation that explores the questions: Does this takeaway offer a healthy, sustainable, affordable and economically viable takeaway? If so, how?

We have completed a number of interviews with the business owner and manager, conducted field visits to the business and surrounding areas and performed data collection feasibility assessments. We plan to complete additional interviews, field visits, documentary analysis and workshops.

Theory of Change

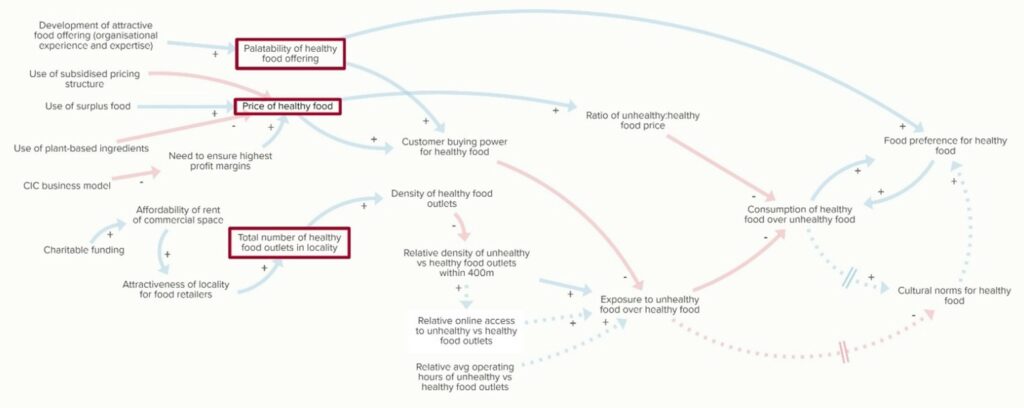

See the image below. We hypothesise that the takeaway will target the nodes of the out of home causal loop diagram highlighted in red. The inputs into these nodes are presented to the left and the outcomes to the right, progressing from short-term to long-term.

Proposed outputs

One or two peer reviewed papers. Introductory film describing our work. Follow up film describing our findings.

Research team

- Dr Jean Adams | MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge

- Dr Catrin Pedder Jones | MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge

- Dr Alexia Sawyer | MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge

- Dr Soujanya Mantravadi | Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge

- Dr Kehinde Adeosun | Institute of Population Health – University of Liverpool

- Dr Rachel Loopstra | Public Health, Policy & Systems, University of Liverpool